Stepped hull design is over 100 years old, but modern boat builders are adopting the technology now more than ever. Jon Mendez offers his advice on how to drive a motor boat with a stepped hull

Putting a step into the hull of a boat is not a new idea, versions of it have been around for more than 100 years. Done well it can deliver the holy grail of greater speed and better fuel economy. It works by introducing air under the hull that acts as a lubricant between the boat and the water.

Some stepped hulls use deck-mounted scoops and ducting to funnel air into the hull steps, whilst others simply extend the steps out through the chines so they can suck air in from the side.

Traditionally, a single step was employed but these days two-, three- and even four-step hulls are increasingly common.

The desire for greater fuel efficiency is driving the latest trend, with everyone from princess to Axopar and Saxdor now adopting them.

Other benefits, aside from looking cool, is that stepped hulls tend to ride softer and flatter than a conventional unstepped hull. But good ideas often have a down side and stepped hulls can become unpredictable when turning at speed.

In the worst-case scenario they can even spin out during a sharp turn – often referred to as hooking – when the bow digs in and the stern swings violently round it.

This tendency can be exacerbated by trimming the bow down too far or by slowing down too quickly mid turn, especially if you’ve also got the drive trimmed out to increase running efficiency.

Both these actions cause the stern to lift, to the point at which it can lose grip and slide sideways across the surface.

Article continues below…

How to handle a single shaftdrive boat

How to navigate overfalls in a motorboat: 6 top tips

Stepped hulls are more prone to this because the steps break the contact with the water and allow the hull to ride on two or three small planing pads rather than one longer continuous one.

The safest option in most boats, but especially stepped hulls, is to avoid turning too tightly, be careful not to slow down dramatically, just before or during a turn, and to maintain a balanced throttle throughout, so the boat’s speed and angle of attack don’t change.

Every turn slows the boat to some degree, as the lean immerses more hull and causes more drag, so by using a bit more throttle through the turn helps counteract this and reduces the chance of dropping the bow and causing it to catch.

Good design helps as well. The Cormate Utility 23 we used to illustrate this article, for instance, has a ventilated Monostep in the centre of the hull. The vertical edges of this step add extra bite on the water that help prevent any stern slip. This section of the transom is also brought further forward and raised, allowing the engine to be mounted higher for extra enhanced efficiency.

At sea this translated to rapid acceleration with minimal bow lift needing almost no fore and aft trim on the outdrive leg once planing, as the efficiency was already designed in.

The very flat angle of attack meant that the step was able to introduce plenty of air under the hull, giving a really well controlled and cushioned ride. I could not get the stern to slide, let alone hook, even by adding excessive trim and pushing it irresponsibly hard through turns. Clever stuff.

Photo: Richard Langdon

First step

This first step cuts in a straight line right across the beam to the chines, and draws air in from the side.

Some boats have a scoop on the foredeck sending air down a tube to the middle of the step.

Photo: Richard Langdon

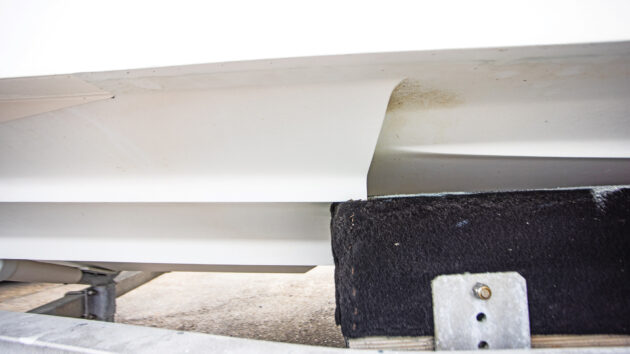

Second step

The second ‘monostep’ also draws in air from the side but the middle section extends further aft than the first one to increase the boat’s grip and stability.

Photo: Richard Langdon

Third step

This photo shows the third step and central tunnel.

Note the vertical hard edges on the outside of the central moulding and the inside of the tunnel, giving much greater lateral adhesion in turns.

Photo: Richard Langdon

Running angle

At speed the Cormate runs very flat and takes a bit of getting used to.

There is no hump speed as you accelerate and it pops onto the plane without any drama.

Photo: Richard Langdon

Turning

When turning, that same flat angle of attack is apparent and even with excessive use of the trim tabs and throttle i could not get the hull to unstick or slide out (hook).

Photo: Richard Langdon

Flat wake

Another characteristic of a stepped hull is a very flat wake, as the reduced wetted surface area causes less disturbance and allows the propeller to run horizontal to the sea surface.

If you enjoyed this….

If you enjoyed this….

Motor Boat & Yachting is the world’s leading magazine for Motoryacht enthusiasts. Every month we have inspirational adventures and practical features to help you realise your sailing dreams, as well as tests and news of all the latest motorboats.

Plus you’ll get our quarterly Custom Yachting supplement where we share the last on offer in the superyacht world and at the luxury end of the market.

Build your knowledge with a subscription delivered to your door. See our latest offers and save at least 30% off the cover price.

Note: We may earn a commission when you buy through links on our site, at no extra cost to you. This doesn’t affect our editorial independence.

If you enjoyed this….

If you enjoyed this….